On agentic coding, sense of urgency and social lag

/ 15 min read

Table of Contents

This day a year ago I wrote about my personal struggles with AI slop addiction - the dopamine loops, the “just one more prompt” cycles, the way generative AI triggers the same obsessive patterns I’ve dealt with since my Ultima Online days.

Since a while I’ve been trying to make sense of what’s happening in the AI coding agent space - the hype, the almost cult-like dynamics in some communities - and I kept feeling like I’d seen this before. Not just in social media, but further back. The same patterns, the same promises, the same anxieties dressed up in new vocabulary.

Social Lag

There’s a gap between what a technology makes possible and what our social structures can healthily accommodate. That’s social lag.

The telegraph arrives, and suddenly messages cross oceans in minutes instead of weeks. But the norms for how to use it? The boundaries? The etiquette? Those take decades to develop. In the meantime: fraud, spam, the anxiety of being always reachable, and utopian predictions that instant communication will bring world peace.

Each technological wave crashes into a society still adapting to the previous one. Some are still figuring out email boundaries. We’re nowhere near adapted to social media. And now we’re adding another layer.

This lag isn’t just about learning new tools. It’s about the slower work of building social structures, developing healthy norms, recognizing when something is burning us out versus helping us thrive. That work happens on human timescales, not product launch cycles.

The Whale-Ship Is Also a Factory

In 1953, C.L.R. James sat in a detention facility on Ellis Island, awaiting deportation during the McCarthy era. While there, he wrote a book about Herman Melville’s Moby Dick called Mariners, Renegades and Castaways.

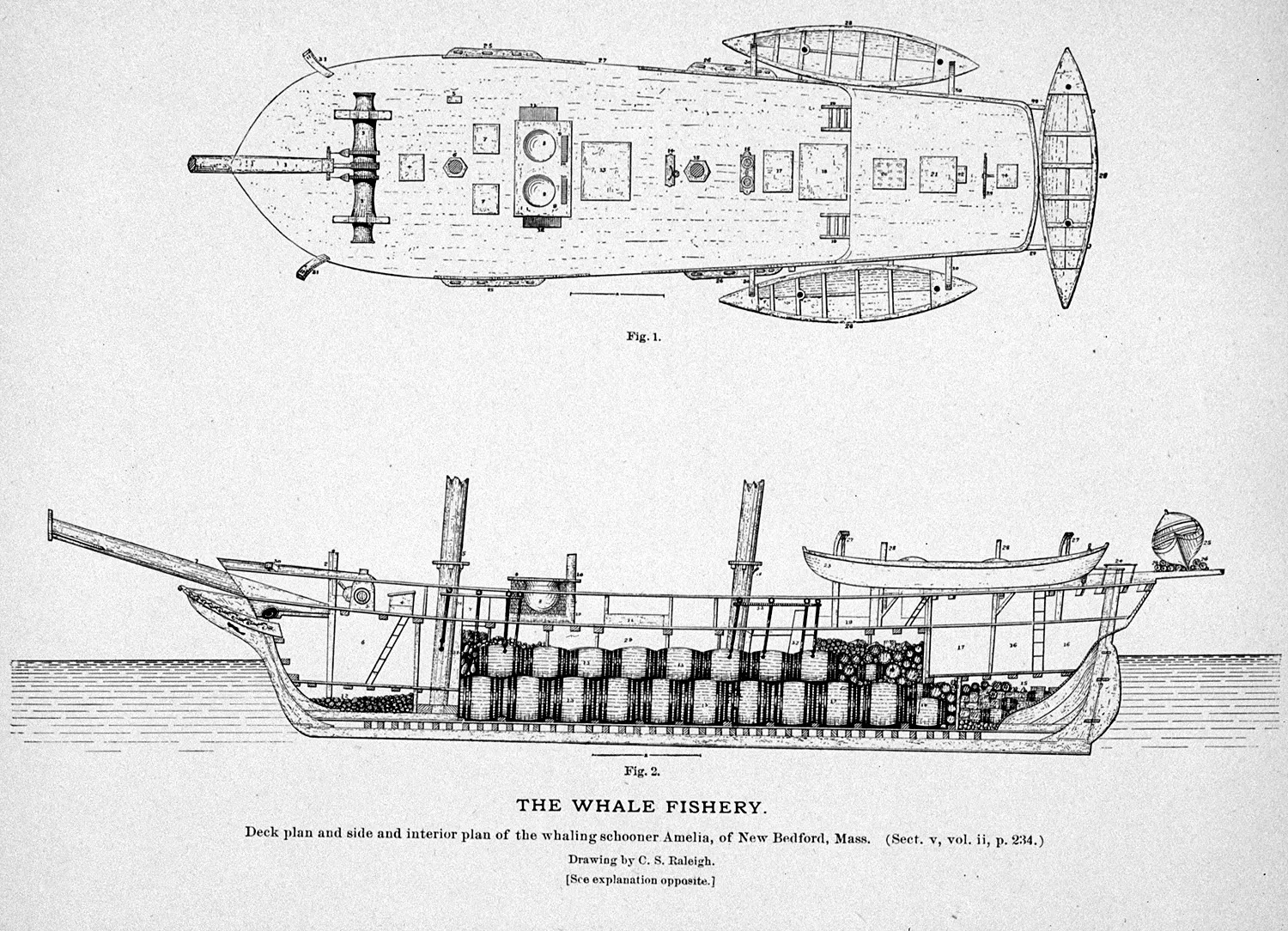

Deck plan of the whaling schooner Amelia of New Bedford, Massachusetts. The whale-ship as industrial blueprint. Source: Cool Antarctica

Deck plan of the whaling schooner Amelia of New Bedford, Massachusetts. The whale-ship as industrial blueprint. Source: Cool Antarctica

James saw Ahab’s ship as an industrial workplace. Ahab wasn’t just a madman chasing a white whale - he was a prototype of the obsessive “captain of industry,” treating his crew as what Melville called “manufactured men.” Ahab’s rejection of reason (he literally smashes the ship’s navigation instruments) wasn’t individual madness but a kind of totalitarian management style that would become all too familiar.

The Pequod extracted whale oil to light the lamps of industrialization. The social structures of the time couldn’t keep pace with the extraction economy’s demands. Workers were disposable. The captain’s obsession was the company’s obsession. Wait, is Ahab a tech bro prototype?

Dracula Isn’t Really a Vampire Novel

In 1993, German media theorist Friedrich Kittler published “Dracula’s Legacy”. The book became part of an early bunch of media literacy related books I absorbed in the late 1990s.

His argument, in a nutshell: Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is not really about vampires. It’s about the terror of a new technological epoch, an account of bureaucratization.

How is Dracula actually defeated? Not by stakes through the heart or garlic. He’s defeated by information processing. Mina Harker, the “New Woman” operating the typewriter, transcribes journals, phonograph recordings, newspaper clippings, and telegram messages. She creates a database. The monster is tracked down through bureaucratic efficiency.

A Blickensderfer typewriter, the kind of machine Mina Harker might have used to defeat Dracula. Source: Wikipedia

A Blickensderfer typewriter, the kind of machine Mina Harker might have used to defeat Dracula. Source: Wikipedia

Kittler’s point is that the real anxiety in the novel isn’t about an ancient evil. It’s about a world “unfamiliar and aggressively technologized, populated by machines that encroach into all areas of life and choreograph new types of behavior and social formations.” The Daily Telegraph of London declared that “time itself is telegraphed out of existence.” Of course the telegraph also brought fraud, spam (yes, telegraph spam was a thing), and the anxiety of being always reachable. Social lag in action: the technology arrived, the healthy norms took generations.

The Generational Pattern

I’ve been following Danah Boyd’s work sporadically since the mid-2000s, back when she was doing research on how teenagers used MySpace and Facebook. At the time, the moral panic was all about online predators and kids losing their social skills. The usual.

What Boyd found was different. After years of actually talking to teenagers about their online lives - documented in her 2014 book It’s Complicated - her core insight:

And this part is crucial:

There’s something comforting here: each generation panics about the next, and each time the kids turn out mostly fine. The moral panics about MySpace, then Facebook, then Twitter, then TikTok - each time, the anxiety was that this technology would fundamentally corrupt young people. Each time, teenagers were basically just being teenagers, using new tools to do timeless teenager things.

But here’s where it gets complicated.

When the Platform Is the Problem

In her 2017 piece “Hacking the Attention Economy”, she documented something fascinating: young people learning to game the very systems designed to capture their attention.

I spent 15 years watching teenagers play games with powerful media outlets and attempt to achieve control over their own ecosystem. They messed with algorithms, coordinated information campaigns, and resisted attempts to curtail their speech.

This is social lag closing in real-time. Digital natives developing new literacies, learning to manipulate the systems that were supposed to manipulate them. The cat-and-mouse game between platform design and user adaptation.

But there’s an asymmetry. The platforms have changed. The early internet - the one I grew up with in the 1990s - was weird, hobbyist, less commercial. People built things because they were interested. Communities formed around shared obsessions, not engagement metrics.

Social media changed that equation. These platforms aren’t neutral mirrors. They’re capitalist enterprises optimized for engagement, which in practice means optimized for addiction. The algorithmic feed doesn’t just reflect human nature - it deliberately amplifies the content most likely to trigger emotional responses and keep you scrolling.

Cory Doctorow has given us the vocabulary for this process: enshittification. The term - which won Word of the Year from the American Dialect Society in 2023 - describes how platforms decay:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

— Cory Doctorow, “TikTok’s Enshittification” (2023)

The generational panic isn’t always wrong. Sometimes the previous generation’s worry isn’t just “kids these days” conservatism - sometimes the platform really is engineered to be harmful. The social lag here isn’t just about adapting to new technology. It’s about adapting to technology specifically designed to exploit the lag, to move faster than our defenses can develop.

Centaurs and Reverse-Centaurs

Doctorow offers another framework that cuts to the heart of the current moment. In his writing on AI-assisted work, he distinguishes between two types of human-machine relationships:

Centaurs are people assisted by machines - workers who get to decide how and when they use AI tools. The human head directs the horse body. The machine extends human capability.

Reverse-centaurs are people conscripted into assisting machines - workers with AI forced upon them by bosses who hope to fire their colleagues and increase their workload. The human becomes the accountability sink, absorbing blame for the machine’s inevitable errors.

It’s easy to understand why some programmers love their AI assistants and others loathe them: the former group get to decide how and when they use AI tools, while the latter has AI forced upon them by bosses who hope to fire their colleagues and increase their workload.

— Cory Doctorow, “Bad Vibe Coding”

This distinction reframes the entire history I’ve been tracing. Each major technological transition produces anxiety about where humans stand in relation to the machine. Will we control it, or will it control us? Will we be centaurs or reverse-centaurs?

The Factory Perfected

Each major technological transition seems to produce its own media (books, movies, memes) that captures this anxiety.

The whale-ship as factory in Moby Dick: Melville’s “manufactured men” are proto-reverse-centaurs - workers disposable to the captain’s obsession, their humanity subordinated to the extraction economy.

Dracula: the monster defeated by information processing. But notice - Mina Harker is a centaur. She controls the typewriter, the phonograph, the telegram. The technology extends her capability. She’s the human head directing the bureaucratic machinery. That’s why the heroes win.

The Matrix (1999) inverts this completely. The machines have won. Humanity has become the ultimate reverse-centaur - bodies suspended in pods, feeding the very system that enslaves them. Humans as batteries. The factory perfected.

The horror of The Matrix isn’t just enslavement. It’s that the enslaved don’t know they’re enslaved. The simulation is comfortable enough that most people don’t want to leave. The social lag is total: humanity never developed the structures to resist, and now resistance requires unplugging from reality itself.

Neo’s journey is the journey from reverse-centaur to centaur - from being controlled by the system to controlling it. But the film is honest about the cost: you have to give up the comfortable simulation.

What About Now?

Maybe Doctorow is this time’s Kittler. His frameworks - enshittification, centaurs and reverse-centaurs - give us vocabulary for what’s happening.

But you don’t need a media theorist to notice when the names tell on themselves.

One of the popular agentic coding tools is called Gastown. The Mad Max reference is entirely intentional. Steve Yegge’s manifesto describes it as “Mad-Max-Slow-Horses-Waterworld-etc-themed.” The terminology is all wasteland: worker agents are called “Polecats” (like the War Boys), projects are “Rigs” (like war rigs), work units travel in “Convoys,” and the orchestrating AI is “The Mayor.”

In Fury Road, Gas Town is the oil refinery that produces “guzzoline” for the wasteland economy. It’s controlled by a grotesque figure called The People Eater. It trades fuel for water and ammunition in an endless extraction loop. War for energy and energy for war - that’s the whole economy. Fury Road is basically a dieselpunk Marxist critique. Civilization ends, but the extraction economy continues, just more brutal and more honest about what it’s doing.

Yegge in a follow-up post: “Gas Town will go from a self-propelling slime monster to a shiny, well-run agent factory.” And: “They have built workers when I’ve built a factory.” There it is again. The factory. At least we’re being honest about the aesthetic now.

Thing is, IMHO: If you’re convinced you’ve discovered the next big thing and want it to stick, spend some time on naming and metaphors. GasTown might be a fun twist. But it’s not a sustainable naming scheme. I mean, why pick the bad guys, why pick a reference to a dying technology? Once something like that sticks, it’s hard to get rid of it again. Think of gits master branches or master/slave terminology and how long it took us to abandon that.

Signs of Unhealthy Communities

The crypto plot twist is a bit telling. There’s already a $GAS meme coin attached to an agentic coding tool - one that subsequently collapsed in what Wikipedia describes as “an apparent rugpull.” When cryptocurrency speculation shows up in a developer community, it’s a signal. It means the community has attracted people optimizing for extraction rather than building. The enshittification has already begun.

But that’s not the only sign.

Developers describe entering fog states during extended agent sessions, emerging hours later with code they don’t fully remember reasoning about. Maintainers burn out publicly under unprecedented demand.

When Memes Outrun Maintainers

Clawdbot lets you run an AI agent on your own hardware, messaging it through WhatsApp or Telegram. It went viral, then the memes took over.

“If you’re not getting a Mac Mini for your @clawdbot in 2026, what are you doing?” Posts like this racked up hundreds of thousands of views. People started buying $599 Mac Minis specifically to run Clawdbot. “I’m so glad I purchased my mac minis before the clawd bot hype.” The hardware became a status symbol, a membership card in the agentic future.

One problem: you never needed a Mac Mini. Clawdbot runs fine on a $5/month VPS or even a Raspberry Pi.

Full disclosure: I’m running Clawdbot on a Mac Studio M1 Max with a thermal receipt printer for daily briefings. You don’t need this. I just wanted it.

Full disclosure: I’m running Clawdbot on a Mac Studio M1 Max with a thermal receipt printer for daily briefings. You don’t need this. I just wanted it.

The maintainer had to push back publicly: “Please don’t buy a Mac Mini, rather sponsor one of the many contributors.” The creator of the tool spending his time correcting viral misinformation about his own project. The hype escaped his control within days.

This is what social lag looks like in fast-forward. The technology ships. The memes mutate faster than documentation can spread. People make purchasing decisions based on vibes and viral posts. The maintainer becomes a fact-checker for their own community.

And it gets worse. Open source maintainers are now facing what one Reddit thread called being “DDoSed by AI slop”. AI-generated pull requests flood repositories - low-effort contributions from people who haven’t read the codebase, haven’t understood the issue, but have access to an agent that can generate plausible-looking code. The maintainer’s job shifts from reviewing thoughtful contributions to triaging AI slop.

The centaur/reverse-centaur question isn’t just about individual developers anymore. It’s about entire ecosystems. When AI agents can generate PRs faster than humans can review them, who’s serving whom? The maintainer didn’t ask for this workload. The maintainer isn’t being paid for this workload. But the maintainer absorbs the accountability while the agent users extract the value.

These are the symptoms of reverse-centaur work. The human serves the machine’s pace, the machine’s demands, the machine’s logic. The accountability flows to the human; the control flows to the system.

The urgency is relentless. “10x productivity.” “Democratized coding.” “AGI by 2027.” These promises have the same cadence as “world peace through telegraph” or “the paperless office.” The hype cycle manufactures a sense of emergency: adopt now or be left behind forever.

And the communities that form around this urgency start to take on cult-like characteristics. Skepticism becomes betrayal. Questioning the timeline becomes FUD. The in-group/out-group dynamics intensify. You’re either building the future or you’re a dinosaur.

These are symptoms of social lag weaponized. The technology moves fast, the hype moves faster, and the pressure to keep up creates communities that aren’t healthy for the people in them.

The Urgency Trap

Here’s what I’ve come to believe: you cannot escape social lag by sprinting into the hype.

The manufactured sense of emergency - the feeling that you must adopt everything right now or be left behind forever - that’s not adaptation. That’s the lag being exploited. That’s the enshittification playbook applied to developer tools: hook them with productivity gains, lock them in with workflow dependencies, extract everything you can before the bubble pops.

Doctorow, writing about the AI bubble:

AI is a bubble and it will burst. Most of the companies will fail. Most of the datacenters will be shuttered or sold for parts… We will have the open-source models that run on commodity hardware, AI tools that can do a lot of useful stuff… These will run on our laptops and phones, and open-source hackers will find ways to push them to do things their makers never dreamed of.

— Cory Doctorow, “A Bubble or a Boom”

The hopeful part of looking at history is that we did eventually adapt. We adapted to the end of whale oil. It took generations, but we built new industries, new labor relations, new ways of lighting our cities. We’re still adapting to social media, but we’re developing norms. Setting boundaries. Recognizing addiction patterns.

The question isn’t whether the technology is good or bad. The question is: are you a centaur or a reverse-centaur? Do you control the tool, or does it control you? Can you choose when to use it and when to step away, or has the urgency colonized your nervous system?

Defending the Centaur Position

Social lag is the time it takes to develop the structures that keep us as centaurs - in control of our tools rather than controlled by them.

Enshittification is the process that turns centaurs into reverse-centaurs - the platform decay that extracts more and more from users while giving less and less back.

Adaptation means building and defending the centaur position. It means recognizing when a tool is helping versus when it’s triggering compulsive behavior. It means being able to step back from a community when it starts demanding more than it gives. It means maintaining enough perspective to evaluate the hype rather than just absorbing it.

The technology will keep evolving whether we sprint or not. The question is whether we’ll still be functional, sane, and capable of doing good work when the dust settles.

Recognizing the Pattern

The whale-ship extracted whale oil. Gas Town extracts guzzoline. The agent factories extract developer productivity. The extraction economy continues, just with different fuel.

But here’s the thing about social lag: it does eventually close. Not through panic, not through hype, but through the slow accumulation of collective wisdom about how to live with new tools without being consumed by them.

Recognizing the pattern doesn’t solve it. But it’s a start. It lets you see the urgency for what it is: a feeling that’s been manufactured before and will be manufactured again. It lets you engage with new technology without letting the hype cycle set your nervous system on fire.

The choice between centaur and reverse-centaur isn’t always available. Sometimes the boss makes it for you. Sometimes the industry makes it for you. But where you do have the choice - and you have it more often than the urgency wants you to believe - choose to keep your hands on the reins.

We’ve done this before. We’ll do it again. The question is how much we burn ourselves out in the meantime.

If you want the way more personal version of this - how these technologies specifically trigger my own addictive patterns - I wrote about that a year ago.